Benefits of open-source, digital course content extend beyond savings

Author: Dave Roepke

This is an archived story. The content, links and information may have changed since the publication date.

Author: Dave Roepke

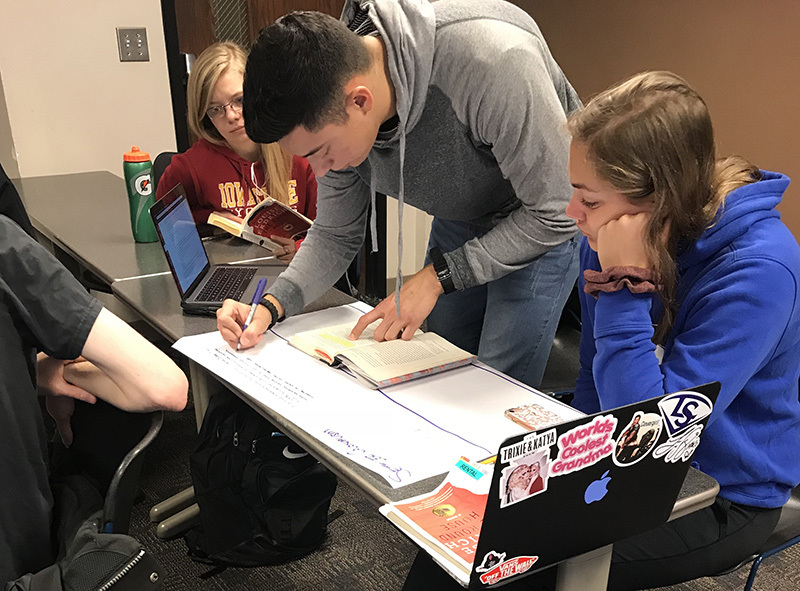

Students in Jen McClung's Native People in American Culture class work on a poster illustrating a theme from one of the course's readings. Photo courtesy of Jen McClung.

Jen McClung and Matthew Clancy both taught classes this year using open educational resources (OER), which are open-license course materials free for students. For the most part, the similarity ends there.

McClung, a senior lecturer in English, designed from scratch lesson plans for a new course, Native People in American Culture, that aimed to keep a class of about 50 students intimate. Clancy's section of Principles of Microeconomics was a lecture for about 270 students that closely tracked the free digital textbook the economics lecturer selected.

Check out the resources and support available on the new OER website, including personalized consultations, guides for finding and publishing open-license content, a list of ISU faculty who are OER trailblazers and the application for a Miller Open Education mini-grant.

To inquire about the immediate access program, email immediateaccess@iastate.edu.

But there's another parallel that has nothing to do with cost. Both instructors selected their course content exclusively because it fit how they wanted to teach.

Though the financial impact of OER and other affordability initiatives is important, especially as tuition rates continue climbing, it's not their only advantage, said Abbey Elder, open access and scholarly communication librarian. There are significant educational benefits, too. For instance, OER course content can be edited and updated frequently and simply, personalized for teaching styles and accessed by students on the first day of class into perpetuity.

"There are pedagogical reasons why OER is more than just affordable content," Elder said.

For years, Clancy had his eye on the free digital textbook he used last fall to teach Econ 101, which saved the students in his course section roughly $30,000.

The book, "The Economy: Economics for a Changing World," came out after his first stint teaching 101 as an Iowa State doctoral student in 2014. Published by a nonprofit, the book emphasizes modern concerns and realistic applications, avoiding the impression that perfect competition is an economic default mode.

"It's sort of a rethinking of what we want to cover and how we want to reflect contemporary issues and economic research," Clancy said. "I just really liked it. It teaches economics the way I like to teach it. If it had cost money, I still would have assigned it."

In addition to its treatment of concepts, the text embraces its electronic nature, he said. Charts and other figures include multiple animated layers, and video examples are common. Teaching from the book reinforced his preference for digital engagement and easy-to-edit text.

"If there are good open-source options, there's no reason why instructors wouldn't want to adopt them," Clancy said. "It's all about the right text. That's what drives people."

Finding a useful textbook always has been elusive for some subjects, and in those courses, OER can be especially appealing because its adaptable and shareable. Clancy is using open-license material to build a new class he's planning on the economics of innovation. McClung did the same last fall when she debuted her new course.

"I pretty much knew I'd have to design my own materials. One of the challenges in this field is the lack of resources," she said.

Designed as a more modern-day version of an American Indian studies introductory course that had seen class sizes grow from the low 30s to 50, McClung incorporated her interests in team-based learning and visual thinking in constructing the semester's six modules.

The team structure gave students a more personal learning environment, which she considers crucial in a class where some cognitive dissonance is expected. The groups identified and illustrated themes in readings, which required them to discuss and translate to imagery their ideas about, say, media coverage of the Standing Rock pipeline protests or Louise Erdrich's novel, "The Round House."

"It succeeded beyond my wildest imagination," McClung said. "In a nonliterature class, I'd say 90 percent read the whole book. That's something teachers dream about."

The flexibility of the course design will keep it current as new issues for native people emerge, she said. "For this discipline, I think that's particularly important, not being locked into a textbook," she said.

Creating a course from the ground up is a heavy lift. McClung said a more piecemeal approach would be preferable, if possible. But she did receive a Miller Open Education mini-grant to help. Applications are open through April 15 for the next round of grants, which can be awarded for identifying, adapting, integrating or creating open-source content.

While OER saves students money, it's a fraction of the savings generated by the ISU Book Store's immediate access program, which digitally delivers course content from commercial publishers. The content is automatically available to students through Canvas, at steep discounts negotiated by the bookstore. Last fall and this spring, students paid a combined $2.5 million less for those materials than they would for the physical versions, more than double the $1.1 million saved in the fall and spring of 2017-18, according to store data.

Heather Dean, the store's assistant director, said the savings could double again in 2019-20. This year's expansion was driven by adding Pearson, ISU's most-adopted textbook publisher. Pearson joined the second-most popular publisher, McGraw-Hill, which already had a digital delivery contract with the bookstore. Next year, the store expects to add more large academic publishers, making most textbooks eligible for immediate access.

"Then it's just a matter of faculty choice," Dean said. "For faculty, it's about quality of content over price, and it'll always be that way."

As with OER, there's an instructional upside with immediate access. Most importantly, it ensures more students have the book. Students can opt out, but most don't. On average, 96 percent of enrolled students receive the material, Dean said. A typical sales rate for a physical textbook is 60 to 70 percent and even lower for the most expensive offerings, she said -- a feedback loop that helps explain $300 textbooks.

"When 20 percent of the class is buying the book, the price goes up," she said.

The nearly guaranteed sales, and pressure from the growing prominence of OER, incentivize commercial publishers to sell textbooks for less and offer more extras, Dean said. One example is adaptive quizzes and homework that adjust in difficulty to match students' aptitude.

"With those kinds of products, you get some data and analytics to gauge the performance of your class," she said.